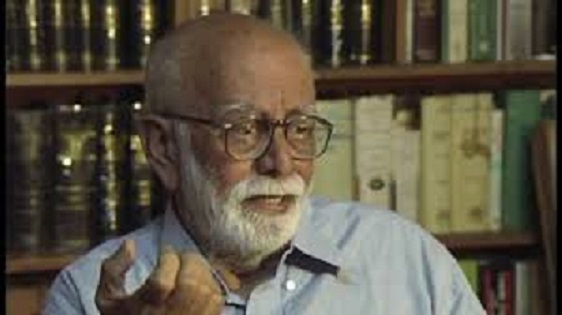

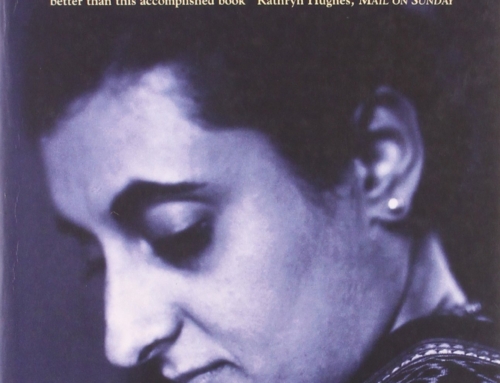

Deepa Dhanraj’s documentary “The Advocate”, on K.G. Kannabiran’s law practice, opens with the visual of a shrivelled finger furiously tap-tapping on a keyboard. As the camera pans upwards, it settles on a grizzled old man with a white beard framing a large head, and tired, wise eyes. “Everything the difficult way,” he chuckles, referring to his stilted typing technique, “that is Kannabiran”. I smiled reflexively, sharing the humour in the implied suggestion that apart from the years of death threats to him and his loved ones, the actual murders of friends, and listening to the first-hand accounts of victims of police torture, the dense, richly-detailed and passionately argued essays that make up KG Kannabiran’s “Wages of Impunity” owe their existence to these one-fingered labours.

KGK, or “Kanna”, as his friends called him, lived his life convinced that the State’s hold over the instruments of power had to be checked, and obstructed, and fought. He allowed this belief to lead him in whichever direction it took. And it took him to all kinds of places. There he stood, leading a band of poets reciting revolutionary poems in court to a disapproving judge. And it was him again, negotiating the release of government officials stuck in the heart of a jungle in East Godavari (the kidnappers only trusted him). It must have been what prompted him to lead the defence of the persons accused of attacking India’s Parliament.

I never forgot, while reading his views on highbrow topics like the right way to interpret the Constitution, the appointment of judges, and the meaning of secularism, that this here was writing from the battlefield; a man who knew the price of the ticket, knew the sweaty odour of the jail cell, met (and befriended) the anarchists who would, if they could, destroy the political system, defended prisoners of conscience during the Emergency and beyond, stood up to the Andhra police, and on at least one occasion, even to the Chief Minister. At the very least, the thoughts of someone who has “worked” the Constitution, and seen its failings, demand meditation and reflection. But Kannabiran does not need his fascinating life story to underwrite the value of these polemics. They have enough originality, shrewdness, and casual erudition to sustain themselves.

Kannabiran looks at police brutality – fake encounters, custodial violence, torture, and the blinding of suspects – and unlike us, he cannot look away. He describes the segregation of, and violence against Dalits with a chilling blandness that leaves the task of registering alarm and shame entirely to the reader. He forces us to examine in detail the draconian anti-terrorism laws we have watched sail past a silent Parliament, and introduces us to the stories of the victims of these laws (“Why protect people who want to overthrow the state?” a judge asked him. His reply: “When such people come to court, it is not their values on trial, but yours.”) He sifts through the evidence in cases nobody would bother with, his trained eye peering deep into the dusty files. This aperçufrom the trial of the Sikh youths who were accused of murdering General AS Vaidya:

“Figuring as witnesses were prostitutes with whom the accused were alleged to have spent time when they were not plotting to kill the general. The propaganda against political dissent is never complete unless dissenters are portrayed as completely degenerate.”

You cannot but think.

For all his gifts, we must take Kannabiran as he is, and not gloss over his prejudices. The limitations of his well-founded suspicions of the criminal justice system are evident, for example, in the unfortunate piece “Sanjay Dutt in the First Person”, in which, while writing as the convicted Bollywood actor, we have to endure such maudlin lines as “I bought the assault rifle to defend myself and my neighbours…” and “My securing an assault rifle is a legitimate act of private defence…” Actually, it was not the one assault rifle – as per Dutt’s unretracted confession, it was three AK-56 rifles, 25 hand grenades, and one 9 mm pistol, besides cartridges. Mr. Dutt’s lawyer was to later write an article titled “Why we should not vote for Sanjay” (when Dutt announced that he would contest elections), in which he made it amply clear that these were not meant for his private security. There is lots to aim at in India’s corrupt, rickety system without using the crutch of inaccuracy. This is, of course, a minor quibble. In this splendid book, Kannabiran takes aim and hits the target almost every time.

I once heard Kannabiran’s eloquent wife, Vasanth, speak of how her husband would tell her that he was “as good” as Nani Palkhivala and Ram Jethmalani, but unlike these two legal grandees, his services were available to the poorest man in the country. I never saw Palkhivala or Jethmalani argue a case in their prime, but based purely on their writings, I think “Kanna” may have been underselling himself.